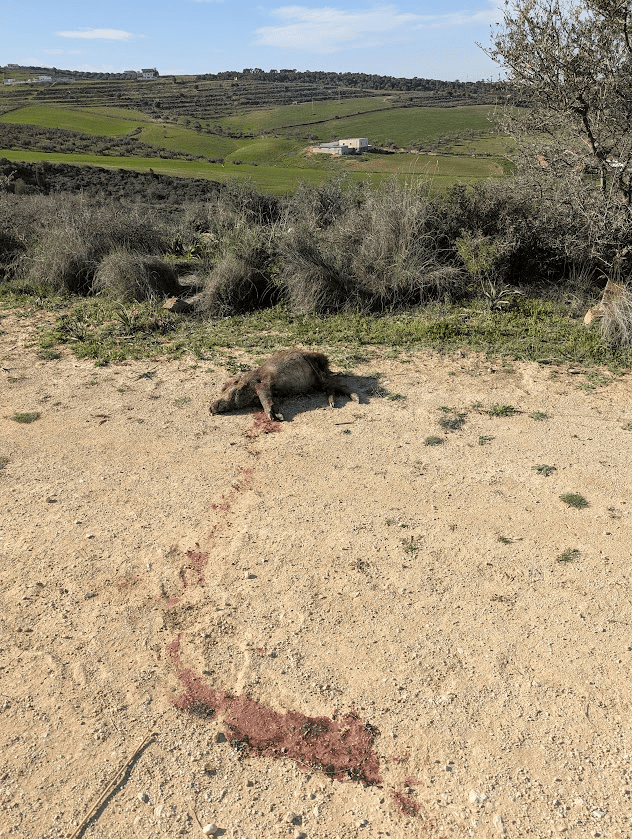

What’s the strangest thing I have done this past week, you ask? I was going to say it’s actually been a pretty average week, but then I remembered the moment where I was crying over Beth Moore’s memoirs playing in my earbuds on Audible while surveying the bloody remains of a wild boar I stumbled across on my running trails, so I’m going to have to go with that. Stooped hands on knees to catch my breath on an isolated trail next to a dead hog in a country where no one eats pork while Beth Moore’s southern drawl lilted in my ears. Just a regular Thursday morning, y’all.

I say “stumbled across” but really I had been following the sandy splashes of blood on the trail for well over a kilometer and glimpsed the shotgun casing in the brush so I wasn’t completely shocked. Having seen the huge black beasts rooting through garbage piles dumped near the trailhead on dawn runs before, I was actually relieved to see it bloated and on its back. Childhood memories of Old Yeller being cut to pieces by a boar had had me keeping my eyes on decent climbing trees as I picked my way down the path, ready for some enraged and injured pig to explode out of the bushes at any moment. But as I turned a bend on the backside of an olive grove, there it lay.

The Beth Moore memoirs are also a bit of a surprise to me having never done one of her Bible studies before and probably holding more of a bias against her than I care to admit. (Though if you had asked me for the precise nature of my prejudice I would have had a hard time answering definitively. Sometimes we are the most judgey about the things we are most like in the big scheme of things.) But a trusted friend had recommended the read and as it turns out, I have had a hard time listening while running on account of how difficult I find breathing while laughing or crying. Regardless of what you think of her (and what I think is not what I thought I thought), the woman can tell a story.

On this particular day, I was listening to Beth describe the fallout of 2016 tweets in which she voiced her dismay at the evangelical support for our then and current president in the wake of the Access Hollywood tapes. Even though I had angry tears on my face as I listened to her powerful words while curiously circling the dead pig, I have a pretty good sense for the poetic and had to tip my hat to the symmetry of the moment before continuing on my way. But more on politics another time.

But yes, other than that, it’s been a fairly low-key week. B’s trip back to the US has been extended by another 5 days. This is hard for the girls and I because we miss him terribly, but we hadn’t yet relaxed into fully anticipating him being home when the call was made to delay his return and so as we round the bend of one more week without him, we’ve still got a good grip on things. School mornings, zoom meetings, language lessons, homework, laundry, groceries, the usual cycle of things. Motorcycle gelato deliveries have helped.

In the moments where solo parenting for weeks on end feels hard, and also when it feels unexpectedly easy, I think of my friend Mona (not her real name). She’s just an acquaintance really. But I get messages from her most weeks. They’re never very personal, even when I gently inquire into how she’s really doing. They are mostly updates, insights into how we can be praying.

Last week marked twenty-three months since her husband was taken from her.

I met her over a year ago on the grounds of the Anglican church where we meet on Sundays. I had never seen her before. She was dressed more like a conservative Muslim woman than most women that sit in this building with the stained glass windows, and had a little girl encircling her legs. Her skin color was what Bryan and I sometimes refer to as “normal”, quoting an Uzbek friend who was once trying to describe a Mexican colleague (“You know, the guy who’s not white, he’s not black, he’s just – how do you say it? Well, he’s normal.”) In other words, she could have been Arab or Italian, Brazilian or Navaho, Indian or Greek. Her impeccable “Airport English” without any clues hidden in a discernable accent made it even trickier to peg her.

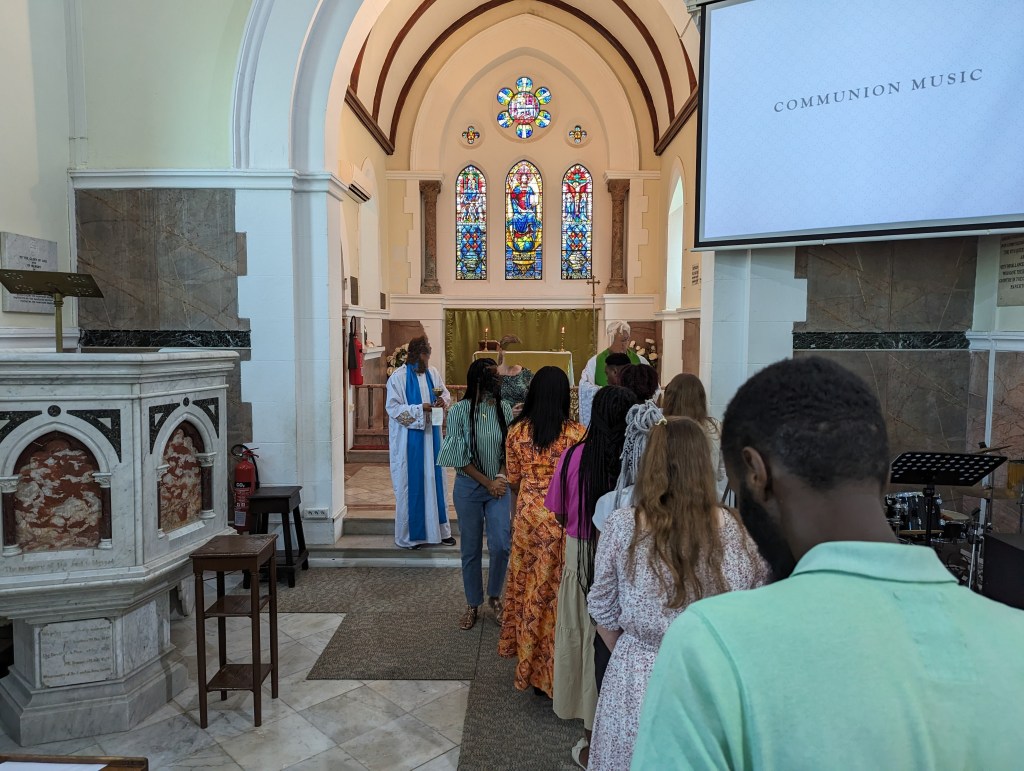

It turns out she is from the country just to the East. Most Sundays we have a number of Christ followers from this country turn up at St. George’s, in some seasons more than others. Two years ago, when there was a serious government crackdown next door, we had quite a few. Mostly young men, well dressed and quiet. Discreet, even here. Politely evasive about their stories in small talk. Where are you from? What do you do? These are surprisingly awkward questions for many of us who gather at 10:30 on Sundays mornings here, all for different reasons. All with different answers. Diplomats, refugees, “workers”, asylum seekers, locals and foreigners, legal and not so much. We worship deeply together and line up to receive the elements from the rector. The body of Christ, broken for you. The blood of Christ, the cup of salvation. Thanks be to God. And then we linger in the garden afterwards, drinking juice and talking about the weather and our kids.

It took me a few Sundays to piece together who Mona was. But when I did, it all made sickening sense. She was Faisal’s wife, the man we had been praying for for months. The man in prison across the border charged with sharing the Gospel. He and about a dozen others were arrested in March (2023). It was weeks before Mona had any communication with him from prison. Months before he even knew that his wife and baby weren’t also in prison somewhere, that they had made it across the border safely.

Mona was ultimately only here a few months before she relocated to another country. In that time, I often found myself wrestling with how to support a sister in this situation. What do you say to the woman in the pew in front of you who is wondering if she will ever see her husband again while we sing another verse of “I Surrender All”? Surely wondering what is happening to him in the meantime. Wondering what to tell her daughter. Mona always kept her cards close to her chest. You didn’t get much access to her emotions, to the questions she surely has for God. I don’t know how much of this was personal (it only seems appropriate that one must earn the right to see those places of the heart), cultural, or just plain survival. But she always said thank you. Thank you for praying for us.

I didn’t expect to keep hearing from her when she moved, but I have been honored to stay in touch. And I am honored to ask you to join us in prayer today too as you read these words. Whether you are reading this on your phone on the other side of the Atlantic from me, on your laptop a few countries to the South of me, or somewhere altogether different far in the future from now (if God is outside of time, can prayers in the future still bless what is currently the present?) – will you pray for Mona and Faisal?

Tomorrow, February 4th, Faisal will be sentenced. As a part of the broken Body we all inhabit together, will you pray for mercy? Pray for God’s dream for the world to come, his will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. I told Mona I would ask this of you.

I’m actually preaching at St. George’s this weekend. Somewhere my grandfather is probably rolling over in his grave knowing I am reading books by Southern Baptist women and preaching at Anglican churches. And bless me, I’m almost as surprised as he is. My hope is that it will be a Sunday of joy, of celebrating the freedom God will have granted Faisal (please, God).

But regardless, we will be there together in the mess of it all. So many odd people with all our strange stories showing up in a singular time and space before fanning back out into the world. Each to the paths God has invited us on where he keeps step with us as we laugh and cry and try to breath at the same time.

Keep the faith, my friends. Even slowly and with your eyes on the bushes, keep running.