I didn’t expect to be freezing cold when I first heard the news of a friend dying in a bombing.

I didn’t expect it to be now, 16 years after we first moved to a warzone. If you had asked me, I would have told you that news would have most likely come when I was sitting on a rope bed under a baobab tree sweating through my long skirt while pouring tea into small glasses for the somber guests that just walked in from the camp. Or maybe I would have heard it on a warm evening in Uganda post evacuation. I would have tried to keep dinner moving along cheerfully for the girls but really my ears would be burning, piecing together the story from the Arabic phrases and long silences syphoning back and forth from where B paced in the backyard on long legs.

But as it turned out, the message of Mubarak’s death pinged on my phone just a few weeks ago, well over a full decade after we lived in the same small town, in an altogether different corner of this continent. I heard the news standing on the edge of a wheezy campfire in muddy blue jeans with new friends in light, slushy rain.

There was no snow when we went with some friends on a camping trip in December, just sleet (let’s be honest, we were glamping really. There were cabins with heat, alhamdulillah). But apparently it does snow in this part of the country occasionally. And when it does, people flock from the capital to the mountains and hire farmers to drive them around in small pickups to take in the wonder of it all. Snow on mosques minarets. I’ve never imagined such a thing.

That’s why they have peaked roofs there. A local friend told me not long ago. Because of the snow. Isn’t that funny? Roofs that aren’t flat? You should go see it sometime.

Despite the rain, we took long walks through cork forests that weekend, along with our feral tribe of children. We talked over steaming cups in smoky firelight. The people we were with are the kind you feel like you have known far longer than is true. Do you ever have the experience of suddenly remembering a dream and thinking – did I dream that last night or 30 years ago? It feels new and terribly old all at once. I sometimes suspect new dreams are made out of the substance of old dreams, so they feel familiar even when it’s the first time you experience it. Anyway, that’s how these people feel to me. New, and yet maybe having always been.

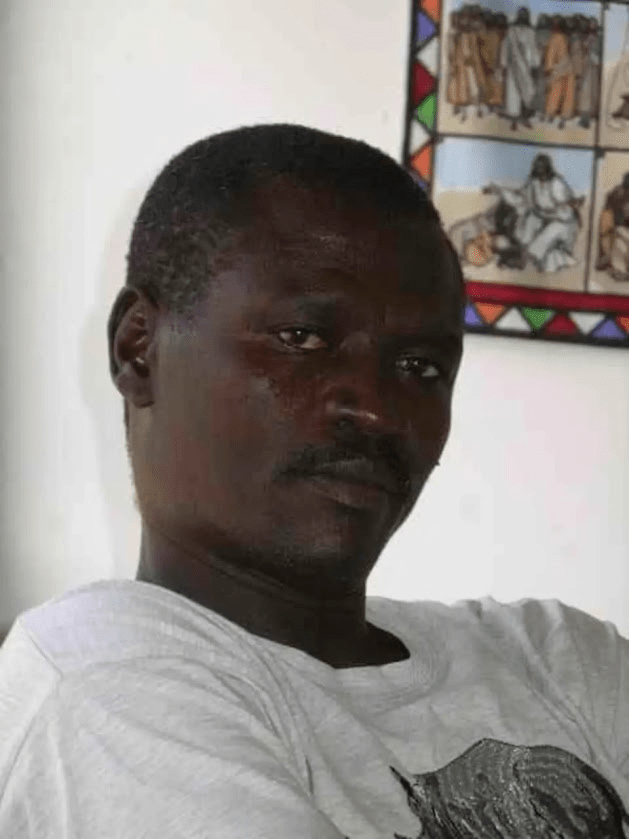

And yet when I saw Mubarak’s face on my phone (it was an old picture so he looked exactly as he did the last time I saw him) and read the words “WFP was bombed yesterday. Mubarak did not survive his injuries” the world suddenly felt a bit tilted. It was like parallel universes were leaking over into one another, worlds that aren’t supposed to overlap bleeding through the boundary lines. The old and new felt confused in a different way.

I’m seeing a cold lake on a cloudy lake but hearing an Antanov buzz a white-hot sky. Two different Arabics twine into a dissonant harmony. The fire is for play and warmth, not for cooking. I’m safe and happy – it’s Christmas time. It’s December, war season. The time of year you have to be ready for anything.

***

One of my pet peeves is people beatifying very normal sorts of people after their deaths or making out a far closer relationship than ever existed on this side of the grave. Neither B nor I had spoken to Mubarak in many years. I don’t pretend to have thought of him much since our lives had flowed down different tributaries. In fact, I was actually surprised to hear that he was still in the Sudans. A well-educated veterinary and fairly cosmopolitan man, I would have expected Mubarak to have settled into a soft NGO office in Kampala or Nairobi at this point. He always talked about Ugandan pineapples – the biggest and the best in the world. Surely he was somewhere that he could eat pineapple any time he wanted to. Surely his kids were getting older. I wouldn’t have expected him to still be “in the field”. I should have known better.

To say Mubarak saved my life is misleading, melodramatic and quite frankly, cringey. But I can’t figure out how exactly to articulate what he did do that is forever etched in my mind with a still shaky sense of gratitude and gravity. If there can be a category called “Saving One’s Life Adjacent” I’d put it there. Because without him I might have walked right back over that landmine.

I saw the landmine the morning after a hard rain. I was walking on to the plot of land where we would soon pitch our safari tent. The cement slab was laid. The latrine almost dug. I was so ready to be off the Samaritans Purse compound and finally in our own space. As I made my way across the short wet grass, a bright red velvet mite caught my attention – the kind that I used to collect in glass jars with my sister as a kid in Kenya. I stopped. And there it was. The smooth arch of the cylinder peeking up from the sandy soil. Green metal, half exposed, half buried, almost coy in its modesty. Six inches from my raised foot.

I hadn’t been in Sudan long at this point. I hadn’t heard any explosions in the background yet, or tanks in the foreground. Thanks to Peter I knew to jump to the side if I ever did ever step on a landmine and not straight up like a fool. This is in hopes the shrapnel just takes your legs and not your life. I was honestly a little bit proud to be a bearer of this kind of knowledge, and in retrospect, probably held it a bit too confidently. (Those of you who know Peter can imagine him telling this to college-kid me: The mines, they sound like water boiling if you step on it. If you hear that…, eh eh eh, you just jump to the side. To the side and then….yah, you just hope for the best. All said laughing a litte too loudly.)

I didn’t hear the sound of boiling water, only goats bleating on the side of the hill that bordered the back of our plot. The day was bright and clear, the sky massive. I confess to a microsecond of dark curiosity and for an instant my foot tingled, hungry to nudge the top edge of the metal loose from the soil. There is so much from those first few months is blurry to me now. So much I don’t remember. But I will never forget the watery rush of fear that flooded my stomach for no clear reason in that heartbeat. Pure, cold horror from the top of my head down to my still hovering toes. With shaky hands, I took a picture and backed away slowly.

But, surprisingly, the fear waned with every step I took away from the object and by the time I found Mubarak I was already half-way convinced of my own overreaction. The last thing I wanted to be was the new American woman seeing UXOs around every termite mound. The sticks that turned into snakes on the path to the latrine at night were bad enough. Mubarak, resident veterinarian on the SP compound (and expert snake killer) looked at the photo on my screen and squinted a little but otherwise had no discernible reaction. He was silent for a moment and I was preparing to be embarrassed when he handed me back my camera and said, “I’m pretty sure it’s an anti-tank mine. You shouldn’t go back on your compound until the UN can clear it.”

I’m not sure why I was so stunned, but I was. It was all still very new at this point and hard to take in. Sudan is a whole vibe. It takes a minute to get used to. There was a landmine where we were planning to put our kitchen.

“Wait, so, just to clarify. It is a landmine or it isn’t?” Like I was just confirming whether someone was or was not coming over to dinner. Mubarak looked at me seriously. “It is a mine and a big one. You guys need to alert the UN. Don’t go back to your compound until it is cleared. Do you understand?”

A few days later we all tucked behind a few sandbags several hundred feet away while a couple of Pakistani peace keepers hit the fuse on some C4 packed around the mine. Later they swept the whole compound. No other mines were found.

My memories of Mubarak beyond the landmine are relatively few. I remember him shaking his head in disgust at the NGO down the road that brought in so many kilos of dog food on their supply flights when people didn’t have enough to eat. The vet spitting on the ground and muttering, “How can you bring in food for animals when people are starving?” I remember him riding with B on Abu Sita, our ATV, to fill and haul huge barrels of water from the reservoir in Korbodi. I remember one night sitting out under the stars, eating rice and beans off of flimsy plastic plates and a strange sound behind us that caused Mubarak to shush us all with a single gesture and then glaze over with intense listening. A dragonfly the size of my face had become trapped in the rain gutter in the building just behind us, making a thrumming noise, a quiet sound very close by that sounded deceptively like a loud noise very far away. When we discovered this, Mubarak laughed but his eyes were bright. It sounded like Nuba Mountains drums. It sounded like home.

We had just over two years in that place with Mubarak and so many others. Those were some of the most raw and exhilarating days of my life. Everything felt more intense, like a drug – the thunderstorms, the color green, the laughter, the malaria, the dreams.

Those years feel like a lifetime ago. Like an old dream, not a new one. But in the old dream, Mubarak went on to live a long life, to see his kids graduate from college, to raise a few cows on a small farm in a country far away from war. Mubarak was one of the many Sudanese who taught us what to do if the planes ever flew over us. How to quickly size up the safest place if you don’t have a foxhole, how to lie down, when it was safe to get up. It feels endlessly shocking to me that, in the end, he died in a bomb dropped from a plane. Why was he still there – there in that town, there in that spot? Why didn’t he do the things he taught us to do? He knew what an Antanov sounded like. He knew where to go.

It feels like the heavy-handed ending of a poorly written novel. Incongruous. Ironic in a tasteless way.

I have a bad habit of gently trying to keep my life within the boundaries of each season. There’s been so many of them. In my mind, it’s just as well for each to enjoy the freedom of their own chapter, their own world unaffected by the mess of the other parts. Worlds colliding has always been disorienting for me. But, go figure, these parts of me, like my dreams, continue to resist easy timestamps and categories.

The past keeps washing up all over my present. Joy sloshes all over my grief. The smell of bakhur or the taste or watermelon or the way one of my daughters looks when reading a book are all threads pulling in tighter, weaving what has beautifully been with what gloriously is and will mysteriously yet be. My own stories keep getting underfoot and tripping me in to focus on the thing lying right there in front of me, waiting to be noticed.

It’s Monday, here in the upstairs room of my house that has a roof you could host guests on if you wanted to. It’s warming up outside and I hear my neighbor’s dog. I have emails waiting to be written, a language lesson to prepare for (this Arabic now, not that one). It will be time to go pick up the kids from school here in just a bit. I don’t recognize the plane that just passed overhead by its sound. But I always hear them.

Glad you are writing again, Ms. Petros. Your prose seems to come from someplace deep with

LikeLike